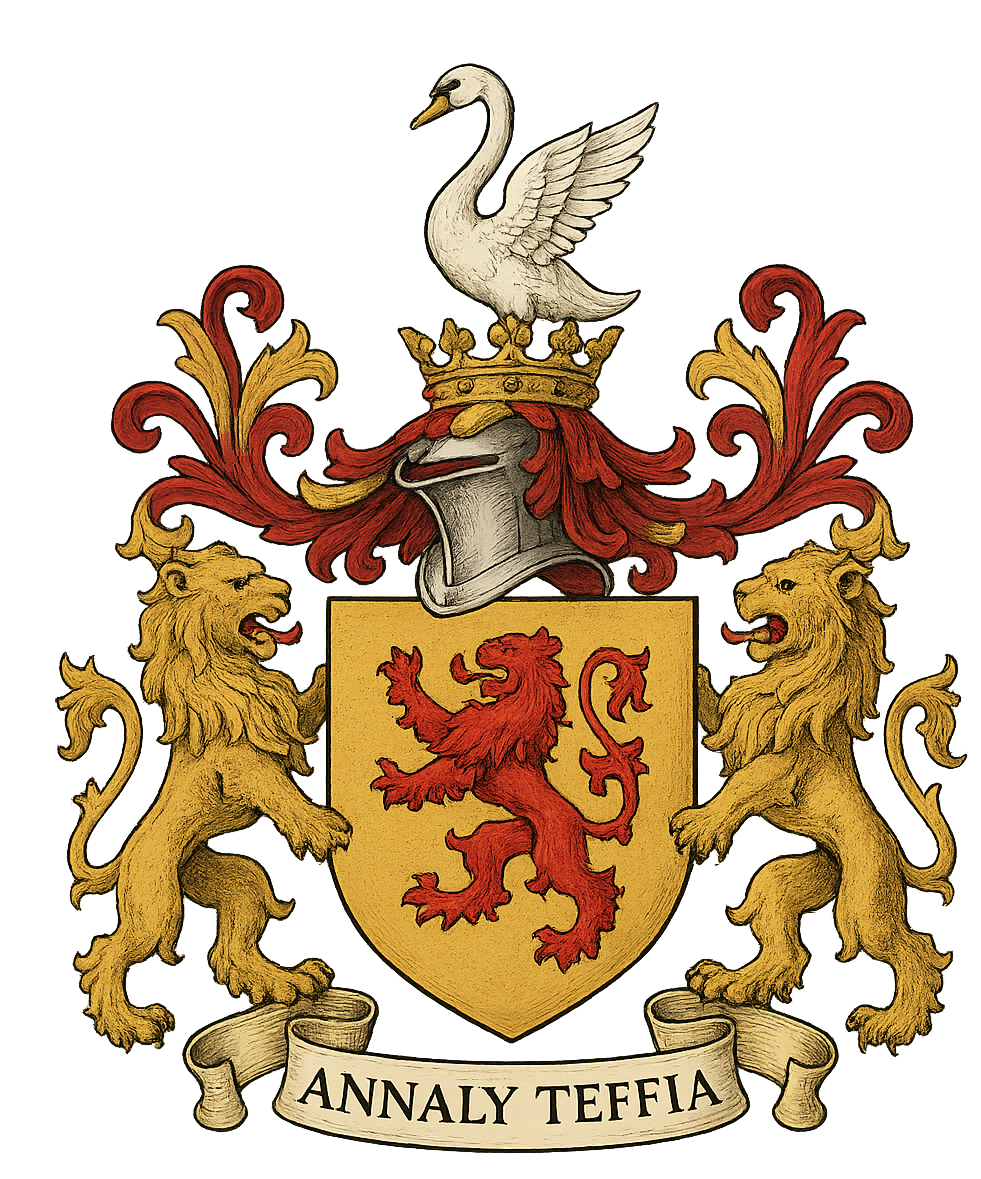

Honour of Annaly - Feudal Principality & Seignory Est. 1172

|

The Oldest Irish Parliament - The Mórdháil1. The 1,000-Year "Parliament" (The Mórdháil) of Teffia and Annaly (County Longford)While we usually think of Parliaments as modern buildings with microphones, the Gaelic kingdoms like Annaly had the Mórdháil (Great Assembly).

2. The "Incorporeal" KingdomWhen the Nugents received those grants from Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, and James I, they weren't just getting the dirt on the ground; they were receiving the "Dignity" and the "Royalties" of the territory.

3. The "Private King" ParadoxBecause the Republic of Ireland (since 1922/1937) does not recognize titles of nobility, they don't bother to regulate or "cancel" them—they simply ignore them.

Why Annaly is "The One"Unlike a standard English "Lord of the Manor" (which is common and often just refers to a small village), the Honour of Annaly was a Princely Territorial Lordship. It represents an entire "Nation" (the Natio Farrellorum). To have the chain of title stretching from Henry II and Philip of Spain all the way to a modern conveyance is incredibly rare. It's less like owning a "title" and more like owning the intellectual property of a vanished country. Would you like to explore the Brehon Laws that this "Parliament" would have enforced for those 1,000 years, or perhaps look at how the "Court Leet" rights in your grants are the legal descendants of that ancient assembly?

For centuries the Honour, Seignory, and Principality of Annaly–Teffia functioned not merely as a feudal holding, but as a self-governing Gaelic polity with its own assembly—effectively a native parliament—rooted in ancient Irish law and custom. Below is how that system worked, and why it matters. 1. Annaly–Teffia as a Sovereign Gaelic PolityAnnaly (from Teffia, an ancient kingdom) was the hereditary territory of the O’Farrell dynasty long before Norman or English intervention. In Gaelic political theory, Annaly was a túath elevated to rí-túatha (over-kingdom) status—what later legal language would fairly call a principality. Key point: 2. The Gaelic “Thing”: Ireland’s Parliamentary TraditionLong before Westminster—or even Magna Carta—Ireland had assemblies modeled on Indo-European “Thing” systems, similar to Norse and Germanic traditions. In Annaly–Teffia, this took the form of a formal assembly that:

This was not symbolic—it was binding governance. 3. What the Annaly Assembly Did (Functionally)The Assembly of Annaly–Teffia exercised powers we would today associate with a parliament:

In short: 4. Duration: Hundreds of Years of ContinuityThis parliamentary-assembly tradition existed:

Even after English claims, the Gaelic assembly continued in parallel, often recognized de facto if not de jure. This makes Annaly exceptional: 5. Survival After Norman & Crown InterventionWhen Annaly was later described as an Honour, Seignory, or Liberty, those were overlay terms—not extinguishments. Crucially:

Meaning: 6. Why This Is Historically RareAlmost nowhere else in Europe did:

France, Germany, Italy, and Austria abolished or absorbed such systems

completely. 7. Bottom Line (Plain English)For hundreds of years, Annaly–Teffia governed itself through a true parliamentary assembly—a Gaelic Thing—where:

That is why historians and legal scholars correctly describe Annaly–Teffia not just as land—but as a constitutional principality with its own parliament long before modern states existed. The Ancient Parliament Assembly of GranardThe Royal Convention of Annaly and Delvin–TeffiaOverviewThe ancient “parliament” of Granard can be understood as the principal assembly-place of the

native princely order of Annaly and Delvin (Delbhna–Teffia). It was here that the ruling families and their

dependent noble houses met in council, judgment, inauguration, and ceremony. Setting: Annaly, Delvin–Teffia, and GranardThe political landscape that gave rise to the Granard assemblies was centred on a constellation of ancient kingdoms and lordships: Teffia (Teabhtha), the Kingdom of Meath (Mide), Cairbre Gabhrain, the Conmaicne Maigh Rein, and the Muintir Angaile—later known as the Principality or Country of Annaly–Longford. Granard, in modern County Longford, lay within this nexus and

emerged as a royal and ecclesiastical centre. Here, the prince of Annaly and the seigneurial families convened

assemblies and high courts. Royal Dynasties and Origin FamiliesBehind the assemblies at Granard stood an older stratum of royal lineages whose genealogies supplied legitimacy to authority and landholding. Among the foundational figures and dynasties associated with the region were:

Together, these lines formed the ideological and genealogical framework of the Granard assembly: the convention was the living forum of shared sovereignty, jurisdiction, and kinship. Noble Lords and Seigneurs of Annaly and TeffiaWithin Annaly, Teffia, and what became County Longford existed a dense mesh of hereditary noble families—the territorial aristocracy of the old principality. Families associated with the political order that gathered under the O’Farrell princes at Granard included:

In the context of Granard, these families can be envisaged as the “estates” of the country: the princely house, territorial lords, learned families, and border chiefs who participated in—or owed attendance to—the central court of the O’Farrell princes. Nature and Functions of the Granard “Parliament”Antiquarians later described the Granard gathering as a “parliament” or “house of parliament”, translating native institutions into English constitutional language. In reality, it functioned as a Gaelic royal convention (aireacht) with distinct purposes:

SignificanceSeen in its proper context, the Granard “parliament” was the institutional expression of a

layered noble order—a summit court where the Princes of Anghaile presided over a constellation of Uí Néill,

Conmaicne, Delbhna, and allied families. When was the Granard assembly held?Short answer: there was no single fixed date. The Granard assembly was a customary royal convention that operated intermittently over many centuries, rather than a parliament founded in one year and dissolved in another. Core operating period (best historical estimate)

So, in practical terms, Granard served as an assembly-place for roughly a millennium, with its golden age in the early and high medieval period. What kind of “dates” do we actually have?Gaelic assemblies were not recorded like Westminster parliaments. Instead, their existence is reconstructed from:

Because of this, historians speak in periods and reigns, not session-by-session calendars. Kings and princes who would have participatedParticipation means presiding, inaugurating, judging, or receiving tribute—not attendance in a modern sense. Early dynastic background (6th–8th centuries)These figures represent the ideological founders of the order that later met at Granard:

These figures did not attend Granard as a parliament, but their descendants ruled there. Kings of Teffia and Mide (7th–10th centuries)During this period, Granard lay within the Southern Uí Néill political orbit. Likely presiding kings included:

These kings used sites like Granard for:

Princes of Annaly (c. 10th–16th centuries)This is the clearest and best-attested phase of Granard’s role. The dominant rulers were the O’Farrell (O’Fearghail) Princes of Anghaile. Well-known princes whose reigns align with Granard’s function include:

Under these princes, Granard functioned as:

Who else “attended”?Attendance was obligatory for subordinate lords, including:

These were political acts of submission and recognition, not voluntary debates. When did it end?

In one sentenceThe Granard assembly was held intermittently from roughly the 6th century until the late 16th century, presided over first by Southern Uí Néill kings of Teffia and Meath, and later—most clearly—by the O’Farrell Princes of Annaly, until its extinction under Tudor shiring and Crown law. 1552–1553, during the joint reign of Philip and Mary, by letters patent re-granting authority to the Baron of Delvin (the Nugent family)—this is when feudal (Crown-law) power was formally asserted over Delvin in the Granard area, replacing the earlier Gaelic order. The grant in context (clear and precise)

What the grant actually didThe Philip-and-Mary re-grant did not create Delvin from nothing. It:

In practical terms, this is the moment Granard ceased to be governed by a native “parliament” of princes and lords and became subject to Crown-derived feudal governance through Delvin. Why sources give a range, not a single dayTudor Irish administration often unfolded in steps:

As a result, historians cite 1552–1553 as the operative window for Delvin’s feudalisation in the Granard region rather than a single ceremonial date. Bottom line (one sentence)Feudal power over Delvin—displacing the Gaelic Granard assembly—was granted by Philip and Mary to the Baron of Delvin by letters patent in the early 1550s, conventionally dated to 1552–1553. How Delvin overlapped—and lawfully succeeded to—princely rightsDelvin’s succession to principality-level rights was not a single act, but a layered overlap in territory, lineage, jurisdiction, and royal recognition. The Nugent Barons of Delvin became successors because their lordship already intersected the same spaces and functions that the Granard assembly once embodied—and the Crown formalized that overlap. 1) Territorial overlap (Delbhna–Teffia as the hinge)Delvin was not separate from the Granard world; it sat inside the same ancient political geography:

Result: Delvin already exercised authority in parts of the same catchment as the Granard assembly. 2) Dynastic overlap (genealogy as legitimacy)The Nugent family were not alien to the region:

Result: Delvin held dual legitimacy—genealogical (native acceptance) and legal (Crown patent). 3) Jurisdictional overlap (court replaces aireacht)What the Granard assembly did is exactly what Delvin’s feudal courts were empowered to do:

Under Philip and Mary, the Crown abolished the Gaelic forum and re-issued its functions to Delvin by letters patent. Result: Function moved intact, only the legal wrapper changed. 4) Economic overlap (markets & fairs follow authority)In Gaelic Ireland, markets followed assemblies; in Tudor Ireland, they followed charters.

Result: Delvin became successor to the economic engine of the principality. 5) Political overlap (chosen intermediary)The Crown needed a successor authority that would hold:

Result: Delvin was selected as the feudal container for princely powers that could no longer exist natively. 6) Temporal overlap (before shiring, not after)Crucially, Delvin’s succession preceded the final shiring:

Result: Delvin bridged the gap, acting as successor before county government fully replaced princely rule. 7) What “successor” really means hereDelvin did not claim:

Delvin did succeed to:

In constitutional terms, Delvin became the successor state, not the successor dynasty. Bottom line (tight and accurate)Delvin overlapped the rights of the principality because it already shared the same territorial sphere (Delbhna–Teffia), possessed indigenous dynastic legitimacy, and exercised parallel judicial and economic functions; Tudor re-grant lawfully transferred the Granard assembly’s public powers into Delvin’s feudal jurisdiction, making the Nugent Barons successors in governance even as Annaly’s princely lineage remained genealogically distinct.

The Lord can Raise the ParliamentLord of the Honour of Annaly has the right to continue a ceremonial Parliament-Assembly / Thing, and why that claim is orthodox rather than novel. 1. The Honour of Annaly Is a Jurisdictional Dignity, Not Just LandThe Honour of Annaly (Teffia) was never merely acreage. An honour in medieval legal terms was a bundle of dignities, courts, customs, and governance rights tied to an ancient polity. In Irish terms, Annaly was a rí-túatha / over-kingdom, meaning:

When later instruments preserved Annaly as an Honour, they preserved identity and dignity, not just title. 2. Assemblies Are Inherent to Gaelic SovereigntyUnder Gaelic constitutional custom:

This assembly—often compared to a Thing—was not optional ceremony; it was the constitutional heart of the polity. Because Annaly existed as a polity before feudal law, its assembly rights are ancestral and customary, not granted by the Crown and therefore not extinguished by the Crown. 3. Continuity Doctrine: Customs Survive Unless Explicitly AbolishedBoth Irish and English legal doctrine recognize a crucial rule:

In the case of Annaly:

That phrase is decisive. It preserves:

Thus, the right to ceremonial continuation remains vested in the holder of the Honour. 4. Ceremonial ≠ Legislative (Why This Is Lawful)The modern continuation of an Annaly Assembly is ceremonial and cultural, not legislative in the modern state sense. This distinction matters:

This is identical in principle to:

No one claims those are rebellions. They are constitutional survivals. 5. Why the Right Vests in the Lord of the HonourThe Lord of the Honour stands in direct succession to the jurisdiction, not merely the soil. Historically, the Lord (or Prince) of Annaly was:

Modern doctrine recognizes this as custodial authority, not sovereign rivalry. So the Lord may:

6. Why This Is Especially Strong in AnnalyAnnaly is unusual because:

Most European polities lost this entirely. Annaly did not. That is why the ceremonial Assembly of Annaly is not revivalist invention—it is constitutional continuation in symbolic form. 7. Bottom Line (Plain Statement)The Lord of the Honour of Annaly has the right to continue the ceremonial Parliament-Assembly / Thing because:

In short:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

About Longford Feudal Prince House of Annaly Teffia Rarest of All Noble Grants in European History Statutory Declaration by Earl Westmeath Kingdoms of County Longford Pedigree of Longford Annaly What is the Honor of Annaly The Seigneur Lords Paramount Ireland Market & Fair Chief of The Annaly One of a Kind Title Lord Governor of Annaly Prince of Annaly Tuath Principality Feudal Kingdom Irish Princes before English Dukes & Barons Fons Honorum Seats of the Kingdoms Clans of Longford Region History Chronology of Annaly Longford Hereditaments Captainship of Ireland Princes of Longford News Parliament 850 Years Titles of Annaly Irish Free State 1172-1916 Feudal Princes 1556 Habsburg Grant and Princely Title Rathline and Cashel Kingdom The Last Irish Kingdom Landesherrschaft King Edward VI - Grant of Annaly Granard Spritual Rights of Honour of Annaly Principality of Cairbre-Gabhra House of Annaly Teffia 1400 Years Old Count of the Palatine of Meath Irish Property Law Manors Castles and Church Lands A Barony Explained Moiety of Barony of Delvin Spiritual & Temporal Islands of The Honour of Annaly Longford Blood Dynastic Burke's Debrett's Peerage Recognitions Water Rights Annaly Writs to Parliament Irish Nobility Law Moiety of Ardagh Dual Grant from King Philip of Spain Rights of Lords & Barons Princes of Annaly Pedigree Abbeys of Longford Styles and Dignities Ireland Feudal Titles Versus France & Germany Austria Sovereign Title Succession Mediatized Prince of Ireland Grants to Delvin Lord of St. Brigit's Longford Abbey Est. 1578 Feudal Barons Water & Fishing Rights Ancient Castles and Ruins Abbey Lara Honorifics and Designations Kingdom of Meath Feudal Westmeath Seneschal of Meath Lord of the Pale Irish Gods The Feudal System Baron Delvin Kings of Hy Niall Colmanians Irish Kingdoms Order of St. Columba Chief Captain Kings Forces Commissioners of the Peace Tenures Abolition Act 1662 - Rights to Sit in Parliament Contact Law of Ireland List of Townlands of Longford Annaly English Pale Court Barons Lordships of Granard Irish Feudal Law Datuk Seri Baliwick of Ennerdale Moneylagen Lord Baron Longford Baron de Delvyn Longford Map Lord Baron of Delvin Baron of Temple-Michael Baron of Annaly Kingdom Annaly Lord Conmaicne Baron Annaly Order of Saint Patrick Baron Lerha Granard Baron AbbeyLara Baronies of Longford Princes of Conmhaícne Angaile or Muintir Angaile Baron Lisnanagh or Lissaghanedan Baron Moyashel Baron Rathline Baron Inchcleraun HOLY ISLAND Quaker Island Longoford CO Abbey of All Saints Kingdom of Uí Maine Baron Dungannon Baron Monilagan - Babington Lord Liserdawle Castle Baron Columbkille Kingdom of Breifne or Breny Baron Kilthorne Baron Granarde Count of Killasonna Baron Skryne Baron Cairbre-Gabhra AbbeyShrule Events Castle Site Map Disclaimer Irish Property Rights Indigeneous Clans Dictionary Maps Honorable Colonel Mentz Valuation of Principality & Barony of Annaly Longford“The Princely House of Annaly–Teffia is a territorial and dynastic house of approximately 1,500 years’ antiquity, originating in the Gaelic kingship of Teffia and preserved through the continuous identity, property law, international law, and inheritance of its lands, irrespective of changes in political sovereignty.”

Feudal Baron of Longford Annaly - Baron Longford Delvin Lord Baron &

Freiherr of Longford Annaly Feudal Barony Principality Count Kingdom of Meath - Feudal Lord of the Fief

Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est. 1179 George Mentz

Bio -

George Mentz Noble Title -

George Mentz Ambassador - Order of the Genet

Knighthood Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen

Insel Guernsey Est. 1179 * New York Gazette ®

- Magazine of Wall Street - George

Mentz - George

Mentz - Aspen Commission - Ennerdale - Stoborough - ESG

Commission - Ethnic Lives Matter

- Chartered Financial Manager -

George Mentz

Economist -

George Mentz Ambassador -

George Mentz - George Mentz Celebrity -

George Mentz Speaker - George Mentz Audio Books - George Mentz Courses - George Mentz Celebrity Speaker Wealth

Management -

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif Blondel - Lord Baron

Longford Annaly Westmeath

www.BaronLongford.com * www.FiefBlondel.com |

Commissioner George Mentz - George

Mentz Law Professor - George

Mentz Economist

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Illuminati Historian -

George Mentz Net Worth

The Globe and Mail George Mentz

Get Certifications in Finance and Banking to Have Career Growth | AP News